On the appeal of fantasy role-playing games

One of the author's D&D dungeon maps

One of the author's D&D dungeon maps

We craved adventure and escape.

When people ask if I played sports in high school back, I tell them I was on the varsity Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) team, starting quarterback, four years in a row. (I was also president of the A/V club. And I memorized Monty Python sketches. And learned BASIC computer programming.) For me, RPGs (role-playing games) like D&D were empowering and exciting, and a clever antidote to the anonymity, monotony, and clique warfare of high school. In lieu of keg parties or soccer practice to vent our angst, we had D&D night. Who needs sports stardom when you can shoot fireballs from your fingertips?

I played every week, sometimes twice a week, from eighth grade to senior year, Friday night from 5:00 p.m. until midnight. JP, my other neighborhood friend Mike, and I first played by ourselves, then found a peer group of other gamers: Bill K., Bill S., Bill C., Dean, Eric M., Eric H. and John. Some of us had endured plenty: my Mom had suffered a brainaneurysm and came home damaged goods; Eric H.’s mom had died, John’s dad had suffered a brain injury similar to my mom’s, and JP was born with a disease that caused brittle bones, cataracts, and stunted growth.

I think on some level we knew we didn’t fit in. Perhaps we were weird. Girls were scarce commodities for us, and our group may have proved that tired cliché that outcasts, dweebs, and computer nerds couldn’t handle reality, let alone get a date for the prom. But nothing stopped us from playing, and the popular kids didn’t really care one way or the other. We were left alone to our own devices: maps, dice, rule books, and soda. It didn’t take long before words like halberd and basilisk became part of my daily vocabulary. Like actors in a play, we role-played characters—human, Elvish, dwarven, halfling—who quickly became extensions of our better or more daring selves. We craved adventure and escape.

One of us would be the Dungeon Master (DM) for a few weeks or months. Games lasted that long. The DM was the theater director, the ref, the world-builder, the God. His preprepared maps and dungeons, stocked with monsters, riddles, and rewards, determined our path through dank tunnels and forbidding forests. Our real selves sat around a living room or basement table, scarfing down provisions like bowls of cheese doodles and generic-brand pizza. We outfitted our characters with broad- swords, battle-axes, grappling hooks, and gold pieces. “In game,” these characters memorized spells and collected treasure and magic items such as +2 long swords and Cloaks of Invisibility and Rods of Resurrection. Then, the adventure would begin. The DM would set the scene: often, we’d be a ragtag band of adventurers who’d met at the tavern and heard rumors of dungeons to explore and treasure to be had. Or some beast or sorcerer terrorizing the land needed to be slayed. Before too long, we’d enter some underground world to solve riddles, search for secret doors, and find hidden passages.

We parleyed with foes—goblins, trolls, harlots—and attacked only when necessary. Or, wantonly, just to taste the imagined pleasure of a rough blade running through evilflesh. We racked up experience points. We test-drove a fiery life of pseudo-heroism, physical combat, and meaningful death. Whatever place the DM described, as far as we were concerned, it existed. Suspended jointly in our minds, it was all real. We were bards, jesters, and storytellers. We told each other riddles in the dark.

And each dungeon level would lead to the next one even deeper beneath the surface, full of more dangerous monsters, and even harder to leave.

At Least There Was a Rulebook

The joy in the game was not simply the anything-can-happen fantasy setting and the killing and heroic deeds, but also the rules. Hundreds of rules existed for every situation. Geeks and nerds love rules. D&D (and its sequel, AD&D, or Advanced Dungeons & Dragons) let us traffic in specialized knowledge found only in hardbound books with names like Monster Manual and Dungeon Masters Guide. As we played, we consulted charts, indices, tables, descriptions of attributes, lists of spells, causes and effects—like a school unto itself, filled with answers to questions about the rarity of magic items, crossing terrain, and how to survive poison.

And we loved to fight over the minutiae. (Sample argument: Player: “What do you mean a gelatinous cube gets a plus on surprise?” DM: “It’s invisible.” Player: “But it’s a ten foot cube of Jello! Let me see that . . . .” Player grabs Monster Manual from DM. Twenty minute argument ensues.)

We could tell a mace from a morning star, a cudgel from a club, and we knew how to draw them. We knew a creature called a “wight” inflicted one to four hit points of damage when it attacked. Could we recharge wands? No. If I died, I could be resurrected, because, according to page 50 of the Players Hand- book, a ninth-level cleric could raise a person who had been dead for no longer than nine days. “Note that the body of the person must be whole, or otherwise missing parts will still be missing when the person is brought back to life.” All good stuff to know. The trolls and fireballs may be fanciful, but they have to behave according to a logical system.

Like in life, fantasy rules were affected by chance—the roll of the dice. And, as if they were jewels, we collected bags of them: plastic, polyhedral game dice, four-, six-, eight-, ten-, twelve-, and twenty-sided baubles that, like I Ching sticks or coins, foretold our fortunes when cast. A spinning die, such as the icosahedral “d20,” could land on “20” (“A hit! You slice the lizard man’s head off and green blood spurts everywhere!”) as often as “1” (“Miss! Your sword swings wide and you stab yourself. Loser!”).

The lesson? Real life thus far had taught me that in the adult world, fate was chaotic and uncertain. Guidelines for success were arbitrary. But in the world of D&D, at least there was a rule book. We knew what we needed to roll to succeed or survive. The finer points of its rules and the possibility of predicting outcomes offered comfort. Make-believe as they were, the skirmishes and puzzle-solving endemic to D&D had immediate and palpable consequences. By role-playing, we were in control, and our characters—be they thieves, magic-users, paladins, or druids—wandered through places of danger, their destinies, ostensibly, within our grasp.

At the same time, we understood that our characters’ failures and triumphs were decided by unknown forces, malevolent or kindly. Such was the double-edged quality of our fantasy life, where random cruelty or unexpected fortune ruled the day. The game was a risk-free milieu for doing adult things.

It was also a relief to live life in another skin, and act out behind the safety of pumped-up attributes. D&D characters had statistics in six key areas: strength, intelligence, wisdom, dexterity, constitution, and charisma. These ranged from three to eighteen. Ethan the real boy’s stats would have been all under 10; his fighter character Elloron’s were all sixteens, seventeens, and eighteens.

And who wouldn't want to be that?

[adpated from Ethan Gilsdorf's award-winning travel memoir and pop culture investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now available in paperback. For more info, see: http://www.ethangilsdorf.com/]

The author's old, worn-out D&D dice

The author's old, worn-out D&D diceA virtual world that breaks real barriers

Rose Springvale is the avatar of Georgiana Nelsen, who cofounded Al-Andalus, a virtual world patterned after medieval Andalus in Spain, where Christians, Jews, and Muslims coexisted harmoniously under Islamic rule. [Courtesy of Rita King and Joshua Fouts]In Second Life's Al-Andalus, a virtual world patterned after medieval Andalus in Spain, avatars of Muslims mix with avatars of Jews and Christians to strive for a more perfect union.

Rose Springvale is the avatar of Georgiana Nelsen, who cofounded Al-Andalus, a virtual world patterned after medieval Andalus in Spain, where Christians, Jews, and Muslims coexisted harmoniously under Islamic rule. [Courtesy of Rita King and Joshua Fouts]In Second Life's Al-Andalus, a virtual world patterned after medieval Andalus in Spain, avatars of Muslims mix with avatars of Jews and Christians to strive for a more perfect union.[from Ethan Gilsdorf's article in the Christian Science Monitor]

Thus far in the relatively short existence of online worlds and virtual communities, less than flattering stories typically float to the surface. The Internet is rife with tales of bad behavior: antisocial "trolls" posting inflammatory messages; players addicted to fantasy role-playing games; and marriages ruined by spouses staying up half the night to flirt in virtual spaces, even proposing marriage to people they've never met in the flesh.

Given the power of negative thinking, it's worth repeating: Not all that happens within the digital realms of monsters, quests, and virtual dollars is evil. Much of the zombie-shooting amounts to people having fun or finding an escape. But some online communities embrace a more lofty mission. They're forging new relationships across the chasms of nationality, religion, and language – long the unrealized dream of some who hoped the Internet could bring us closer.

One such place is Al-Andalus, named after a real nation that once existed in the Iberian Peninsula. From the 8th to the 15th centuries, the spirit of la convivencia, "coexistence," ruled Spain. Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived together mostly harmoniously, and created a vibrant artistic, scientific, and intellectual community.

The volunteers who "built" Al-Andalus in Second Life, the virtual world created by company Linden Lab, wanted to re-create that utopian place, particularly in the wake of the intercultural ill will brewing since 9/11. Only their Al-Andalus is made of pixels, not bricks, and peopled not by humans but their digital doppelgängers, or avatars.

"I'm a pacifist. I'm a mother," says cofounder Georgiana Nelsen, a business lawyer practicing in Houston who in Second Life (SL) goes by "Rose Springvale" (and, informally, the "Sultana"). "I want to always teach 'Use your words, not your hands.' And so this appealed to my personal desire to do something positive in the world rather than continue to foster things that are divisive."

After nine months of construction, Al-Andalus opened its virtual doors in July 2007, and now has 350 contributing members and receives thousands of day-trippers. The democratically run community (and recognized nonprofit) is roughly one-quarter Jewish, one-quarter Muslim, and the remainder Christian and atheist. The massive virtual grounds include a re-creation of the Alhambra and Alcázar fortresses and palaces and the Great Mosque of Córdoba, plus a caravan market, library (run by a Smithsonian librarian), theater, and art center. People can attend a flamenco concert; a meeting; or a religious service in a synagogue, church, or mosque – or even ride a magic carpet for an aerial tour (almost 180,000 have done so).

Read the rest here at the Christian Science Monitor

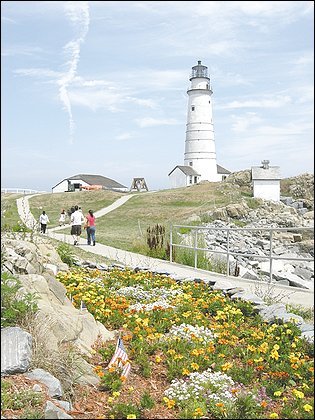

Impulsive Traveler: Boston's Harbor Islands shelter a multitude of surprises

In the ominous opening of Martin Scorsese's movie "Shutter Island," Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo, playing federal agents, take a boat out to a craggy-cliffed island off the coast of Boston.

In the ominous opening of Martin Scorsese's movie "Shutter Island," Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo, playing federal agents, take a boat out to a craggy-cliffed island off the coast of Boston.

"My friends were watching the DVD and said, 'Wow! You have an island like that?' " said Phil Rahaim, a park ranger on the Boston Harbor Islands. He had to tell them, "Not exactly."

"Shutter Island" was partly shot on an island called Peddocks, but none of the 34 real harbor islands actually look much like the movie's CG-enhanced slab of rock. Nor have any of them ever housed an insane asylum conducting experiments with psychotropic drugs.

Geek Out!

Like when the planets align, there are a few times each year when geeks can fly their freak flags high and proud, in vast numbers, and at the same time in different parts of the universe.

Like when the planets align, there are a few times each year when geeks can fly their freak flags high and proud, in vast numbers, and at the same time in different parts of the universe.

This coming Labor Day is one of those weekends.

On the west coast, we have Pax, in Seattle, a three-day game festival for tabletop, videogame, and PC gamers and a general celebration of gamer-geek culture. (And in the other corner, Atlanta, we have Dragon*Con. But more on that another time.)

In fact, Pax calls itself a festival and not a convention because in addition to dedicated tournaments and freeplay areas (The east coast version in Boston this spring had a very cool classic arcade game room, which was amazing! All your fave games like Frogger, Galaga and my fave, Robotron 2084), they’ve got nerdcore concerts from awesome performers like MC Frontalot and Paul & Storm, panel discussions like “The Myth of the Gamer Girl,” the Omegathon event (A three-day elimination tournament in games from every category, from Pong toHalo to skeeball), and an exhibitor hall filled with booths displaying the latest from top game publishers and developers.

But I was thinking that probably the best part of PAX (and similar events like Dragon*Con, the other big fantasy/science fiction fandom event of the year) is this: You get to hang out with kindred folk who love their games and books and movies and costumes. They will argue and defend their fandom universes to the death. They will argue why Tom Bombadil should not have been cut from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. They will battle over Kirk vs. Picard. They will annoy and astound you with their detailed, persnickety knowledge.

In other words, a geek is less what someone loves as it is HOW they love that object of affection. Geeks are passionate about their thang before it became fashionable and long after it’s passed from the public eye. Perhaps that’s the best definition of a geek.

If you’re headed to Atlanta or Seattle this weekend, check here for how to win a free copy of my book Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks, now out in paperback.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of the award-winning travel memoir-pop culture investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms, now out in paperback. You can reach him and get more information at his website www.ethangilsdorf.com.

Pop Ten blog

Ran across this site today --- PopTen "top ten lists and pop culture rants" --- bits like "Top Ten Wi-Fi Connection Names" and "Top 4 reasons NOT to date a European (+ one reason to date a British dude if you must)." And,some nice words about "Fantasy Freak and Gaming Geeks," too:

"Revelatory and balanced Ethan shares his impressions while allowing the people he meets to share theirs. The book quickly becomes about more than just gaming as the discussion leads to larger questions about our escapist society as a whole. ... Gilsdorf takes a Kerouac meets Cliff’s notes approach to Geekdom, and while he met great people along the way it was really about the author’s journey.... His problems are that of the everyman, and although his experience is with geekdom the frustration is universal."

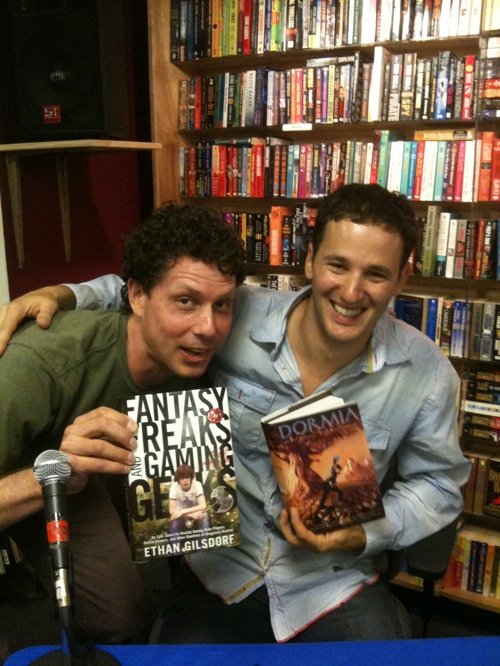

a night with "Dormia"

Last night at the Brookline Booksmith, Jake Halpern and Peter Kujawinski read from (and acted out) their new YA/all-ages novel Dormia. The book tells the story of another young boy (not THAT young boy) with special gifts and a hidden lineage that he gradually figures out on a world-girdling quest.

Twelve-year-old Alfonso Perplexon has a sleepwalking problem -- sometimes he wakes up and find himself at the top of a tree or having accomplished some amazing feat. In his hometown of World’s End, Minnesota, the dad is out of the picture (a familiar theme in Star Wars, E.T., HP, and other boys-to-men coming of age stories).Alfonso and Mom carry on. Then a stranger comes to town, a quirky man who claims to be Alfonso’s long lost uncle. The man tells of the kingdom of Dormia, far in the Ural Mountains, and that Alfonso has the gift of "wakeful sleeping." This lost land is in trouble, and only Alfonso has a chance to save it. So out the door they go, headed for adventure, picking up oddball characters and mishaps along the way.

At the reading, Halpern did a masterful job play-acting some key scenes from the book, and Kujawinski deadpanned the tale of how this team of authors managed to write the book from the distance of New York, Paris, Israel and a Navajo Reservation in northwestern New Mexico. Their story inspired me to try my hand at spinning my own tale, or perhaps collaborating with my pal JP (the dude who taught me D&D; you can read about that in Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks.)

And the funny thing is, there's a 12 year old boy gamer named Alex who I talk to in my book. And I was 12 when I began to play D&D. What's the attraction to age 12 and all this fantasy stuff?

No longer 12 years old: Ethan Gilsdorf and Jake Halpern show off their books

No longer 12 years old: Ethan Gilsdorf and Jake Halpern show off their books

Roll for damage (extra bases)!

In an interesting piece in the NY Times about APBA, a board and dice baseball game is, if not going strong, at least holding its own against video and fantasy league versions of sports games. Like all great subcultures, it's got a devoted following; a recent tournament attracted 76 players. According to the article, "Video games have become increasingly sophisticated, and fantasy sports leagues have surged in popularity, but APBA, like its rival Strat-O-Matic, has stuck to the basic format that made it successful."

APBA, which once stood for "American Professional Baseball Association," is about as old-school as it gets: dice, cards, and dice shakers. And what's most interesting is this geeky twist on who plays--- yes, folks who self-identify as "nerds" and "geeks," lovers of statistics "in statistics-related careers like accounting, teaching math, tax law and financial advising." Nerdy sports nuts --- and as we know, sports is celebrated in our culture. Conjuring magic spells, not so much.Of course, with APBA, no dungeons or dragons are required --- just the fantasy of imagining a winning team (or playing center field for one). An acceptable fantasy for most boys, men (and girls and women, too).

The article points to an interesting turn, too. Brian Wells, the 16 year old kid who has won the tournament a couple times, has been "begrudgingly" accepted by the men. A kid's game is co-opted by adults who then let the kid back in as a member of their tribe.

But also this point -- can an old-school board game (or for that matter, a miniature soldier wargame) capture the imagination of kids when most are used to the spoon-fed action and eye-candy of XBox and Playstation? It's an issue I discuss in Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks, specifically whether a wargame like Chainmail can entrance a 12 year old boy, or whether he's start craving Warcraft after the first hour of snail's pace action.

In the Times article, the kid says that his friends stay home with video games. “They don’t make fun of me,” Wells said. “But they don’t want to get into it. Because some of my friends just don’t have the attention span for all of this.”